by Jennifer Odom

“We’re shearing sheep at the farm. You and your daughter come on out,” Carol Postley told me. We’d struck up quite a chat while sitting back to back working our demonstration tables at the KidZone, part of a Master Gardener event in Ocala. I’d asked about her display of wool and sheep interests. It turned out she’s the founder of Meat Sheep Alliance of Florida.

Sheep in Florida? Wasn’t our state too hot? Aside from zoos, I thought sheep lived up north. So yes, we wanted to visit. I couldn’t resist.

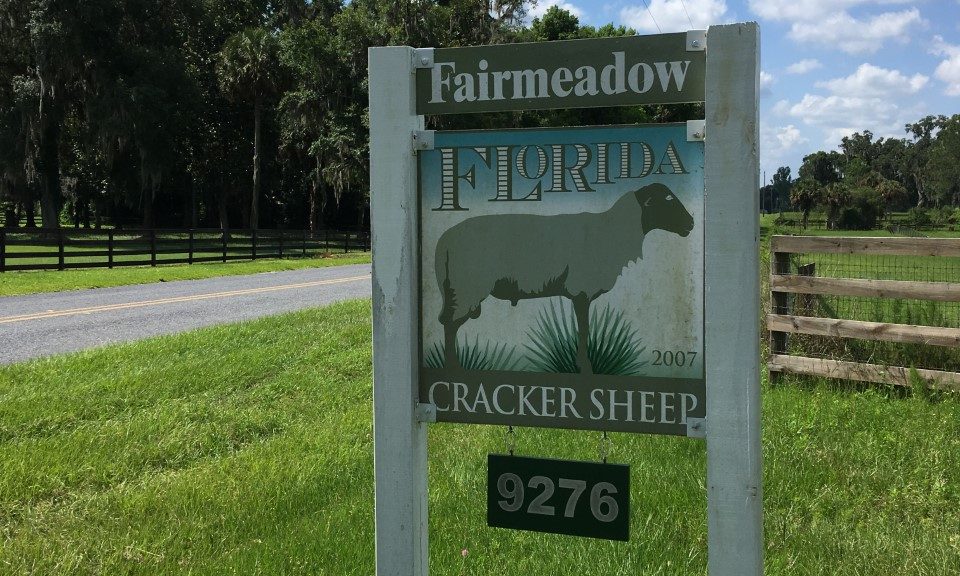

A week or so later Gabbie and I set out in search of her farm. We followed the old Knoblock Road, a shady lane of beautiful ancient oaks and green pastures to her turn-off at the sign that said Florida Cracker Native Sheep.

Farm workers directed us past the barn to a pavilion where we found Carol, natural-born teacher and sponsor of the event, busy about her business of educating and inspiring newbies and fellow farmers about sheep. Her program began with professional sheep shearers demonstrating sheep-holding techniques and proper use of the electric clippers.

A shearing begins by turning a sheep upside down. I’d never seen the underbelly of a sheep before. It surprised me to learn the that the udder, unlike a cow’s, only has two teats, suitable for the twins a sheep usually bears. From there the shearing process moves up and around the legs and back, leaving the sheep very bare, and probably feeling a little chilly. It is customarily done at springtime.

The fleece, or wool, comes off in one large piece, and can be rolled and laid out on tables to allow workers to pick out any undesirable elements or burrs, leaving the choicest part intact.

Though it looks like something else, the very noticeable yucky stuff on the sheep’s wool is lanolin, a thick oil that helps him resist parasites. Don’t worry too much about that, it can be cleaned up. Weeds, seeds, and prickles would be a worse problem. It’s very difficult to clean that out of the wool.

Did you know that hair among the sheep’s wool is an undesirable trait and breeders attempt to breed it out? Those sheep are sent out to be used for meat.

There’s a major difference between hair and wool. Hair, stiff and straight, has a distinct look from wool and after some practice is easy to spot. Its presence in a fleece makes it unsellable, and in a hat or wooly garment will render it itchy and un-wearable. Hair in rugs, though, is quite acceptable.

Who knew?

Decorating the pavilion were woven, knitted, crocheted, and other artistically produced garments and hats. Experts at demonstration tables showed us how to use fiber-straightening machines, carding machines, and how to do peg-weaving.

And if the mention of that yucky stuff still lingers in your sensitivities and bothers your mind, rest easy. A primitive “neolithic wool-cleaning” method using fermentation to get rid of those undesirable impurities was explained by another expert. So rest easy, one doesn’t have to handle dirty wool.

Gabbie reminded me that King David of the Bible herded sheep and was probably familiar with simpler methods of all the skills mentioned above, and most especially this neolithic method of cleaning.

Carol circulated among the guests, and from our common interest in the Master Gardener event, our conversation turned naturally to plants. She was full of information.

No stranger to the use and benefits of scientific testing, Carol informed me of two special and very nutritious forage weeds on the farm. “See that Spanish needle over there?” She pointed toward the lamb pen.“Tests show it contains 25% protein.”

Evidently that’s a very good number.

“People hate that stuff,” I said, recalling how its needle-like burrs stick to everything. “They mow it down and plant pasture grass.”

“And why would they want to do that when it’s got all that protein?” she said. “There’s another nutritious plant like that, the day-flower. It looks a little bit like a wandering Jew.”

“Really?” I couldn’t quite picture this one.

“I’ll see if I can find you one.” Off she scampered to find a sample. In a few minutes she returned with a long stringy weed in her hand.

“Oh, I’ve seen that,” I said. “I pull it out of my flower beds all the time and throw it in the burning pile.”

She grinned. “Again, twenty-five percent protein.”

To think, I’d been burning up good forage. Of course, I don’t have sheep, either.

Carol is not just busy collecting trivia about nutritious forage. She is actively trying to help other farmers in the pursuit of naturally healthy pastures.

CRABGRASS EXPERIMENT

Carol is currently busy lining up an experiment on pasture-improvement through the Marion County Extension office in Ocala. It’s especially targeted for farms with sugar-sand, and it’s not too late to volunteer. (To participate, see contact info at the end of this article).

And Ahem…Who in Florida doesn’t have sand and need pasture improvement?

Carol’s simple experiment requires no more than a plot of land about 50 x 50 feet. Carol will provide the already purchased crab-grass seeds, and Agent Mark Bailey (see below) will supply the details.

The experiment will involve discing the land and planting crabgrass seeds. The owner will have little or no work to do. For those interested in participating and improving your pasture, see the contact information at the end of this article.

Carols’s Florida Cracker Sheep and Their Long History in Florida….

At Carol’s farm, Fairmeadow, she raises a specific breed of sheep I’d never even heard of before. They are called Florida Cracker Sheep.

“The Spanish brought them over,” she informed me, and rattled off a handful of interesting facts about them. She made me want to know more.

After some research, I discovered an article by Ralph Wright, historian of Florida Cracker Sheep Association. It seems that on four or five different occasions Spanish explorers brought sheep over to this continent, and for a variety of reasons released them. These heritage sheep likely descended from the churra sheep of Spain’s estuarine marshes and date back to the 1200’s. The Cracker Sheep Association homepage states: “Florida Cracker Sheep are a heritage breed that developed naturally over the last 400 years and are uniquely adapted to the harsh Florida environment. With their parasite resistance and ability to handle the heat and humidity, they are great for organic farming.” (http://floridacrackersheep.com).

What didn’t kill the sheep in pioneer Florida, then, must have made them stronger. To me it’s amazing, with all the wild animals on the Florida frontier, how anything as mild and gentle as a sheep, who don’t even run fast, could survive at all.

To read Mr. Wright’s complete paper see http://floridacrackersheep.com/history.html.

So sheep, it seems, are not an unusual phenomenon in Florida. And these cracker sheep are particularly suitable for Florida’s environment.

Carol Postley recognized this fact a long time ago. She is an amazing woman full of hard-earned knowledge, and part of a smart group of farmers who steer away from artificial contrivance and diligently work at finding ways to use our God-given nature to best advantage.

I’m privileged to have visited Fairmeadow farm. Great job, Carol, and thank you for the delightful invitation!

If you think you might like to participate in Carol’s pasture grass improvement experiment contact Ag agent Mark Bailey at the Marion County Extension office in Ocala. His contact information is mark.bailey@marioncountyfl.org and phone: 352-617-8400. This experiment will cost approximately $55 to conduct the necessary soil tests before and after the summer forages have been planted.

http://floridacrackersheep.com/history.html

To contact Carol’s professional sheep shearers, see below:

Jonathan Hearne- hearne.jn@gmail.com

Charlotte Crittenden- ccritten@yahoo.com

For participation in the crab grass experiment:

mark.bailey@marioncountyfl.org 352-617-8400

Fabulous post, Jennifer! I had no idea. Makes me want to make a road trip and investigate.

Thank you, Jane, there is so much to see right under our noses.

Great article! I learned a lot and enjoyed reading it. Thanks!